Opened: 1911

Built By: Milton Hess – Farmington, Utah

Location: North of Lagoon

Original Cost: $75,000

Track Length: 1 mile

Area: 40 acres

Despite becoming widely popular in the late 19th century, horse racing was soon on the decline in the United States around the turn of the century. During the Progressive Era, social activists saw racing and the accompanying gambling culture to be an ailment to society. The reform was viewed as a success as the number of race tracks in the nation dropped from 314 in 1890 to only 25 in 1908.

Meanwhile, the sport’s popularity was just reaching an all-time high in Utah. Lagoon had been flourishing in Farmington for about fifteen years when they added their own race track in 1911. Farmington resident Milton Hess was put in charge of constructing the track and its accompanying sructures.¹ Hess had been responsible for the construction of most of Lagoon’s earliest structures such as the original Fun House, Midway buildings and rides like Shoot-The-Chutes. A grandstand was built on the south side of the track with stables on the north and east sides and a large barn to the west. The track straddled the Farmington city boundary and when questions arose about whether the city or Davis County would have jurisdiction over the track, the city proposed annexing the land. Lagoon supported the idea and the change was made.

Lagoon’s Race Track became one of three main horse racing venues for the region along with the Utah State Fairgrounds track in Salt Lake City and the Buena Vista Track at the Weber County Fairgrounds in Ogden. Local horses as well as many from around the world were entered into races at Lagoon. Glen M. Leonard stated in A History Of Davis County, “Racing was good for local businessmen. The season was concentrated in a three week period in the summer and was sometimes repeated in the fall. Supporters rented local cottages and filled hotel rooms.”

Contrary to the excitement and popularity of the sport in those days, anti-racing editorials appeared regularly in both the Salt Lake Herald and the Deseret News. As was common during America’s Progressive Era, community organizations and elected officials were pushing for reform to promote better living conditions in cities. Horse racing was viewed as a central component of the gambling culture and a prime example of the corruption it brought to the cities where it took place. In February 1913, a bill was signed into law by Gov. William Spry that banned racing in the State of Utah.

At that point, owners raced their horses in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho instead and animal sheds were sold off to local farmers. But the new law didn’t mean Lagoon’s new track was completely abandoned. Alternatively, the spotlight shifted to automobile racing. One highlight was in 1914 when a big exhibition race between airplane pilot Barney Oldfield and race car driver Lincoln Beachey took place on the track.² Even when strong winds ripped through the area in November 1919, causing $20,000 in damage to the grandstand and other buildings, the track continued to host big events. For example, a Speed Carnival on Labor Day in 1920 featured many different types of auto races such as a stock car race, free-for-all and reverse gear race.

The pari-mutuel system or “cooperative betting” saved horse racing in other states so it was considered as a means for legalizing races in Utah once again. Charles Redd, a representative of San Juan County proposed a bill to bring horse racing back to Utah under the pari-mutuel system with a committee appointed to regulate all racing in the state. The bill passed and was signed into law by Gov. George H. Dern in May 1925. An article from Utah Historical Quarterly explains,

“Those who voted for the 1925 measure did so because they believed that horse racing had become a clean and respectable sport; that it would encourage local breeders to sire faster, stronger horses; that racing would bring new sources of revenue into the state; and that the sport would give local businesses a shot in the arm. Those who opposed the measure used many of the arguments from a decade earlier. They believed that race track gambling was immoral and a menace to the community. The claim was again made that this was the ‘most vicious form of gambling’ and would bring back the undesirable riffraff that had forced elimination of the sport in 1913.”

Utah Horse Breeding & Racing Association, one of two out-of-state entities that sponsored meets in Utah, spent $40,000 rebuilding and equipping the Lagoon Race Track for 1925. Races were held in Utah once again starting in July of that year. They continually drew large crowds and brought in considerable amounts of revenue for the state. Over time, however, business owners doubted the benefits racing had for their businesses and the public reconsidered the moral effects it had on their communities. By the end of 1926, Charles Redd, the representative who helped to reintroduce horse racing, sought to end horse racing and pari-mutuel betting. His claims of dishonest practices by the State Racing Commission brought about several hearings that never proved the allegations, but brought up enough concerns that horse racing was outlawed once again in early 1927.

Very little has been recorded about what the race track may have been used for after that. The track and accompanying buildings may have been used for events during the Davis County Fair, which was held at Lagoon each August from 1929 to 1942.

The land was purchased by the Paramount Dairy some time during World War II. A history of Farmington by long-time resident, Margaret Steed Hess (wife of the aforementioned Milton Hess) states that during the war, “there was quite a demand for milk at the Bushnell Hospital in Brigham City. This was probably the reason Paramount Dairy representatives, Ezra M. Peterson and his son-in-law, Lynn Richardson, purchased the land for a dairy at the Lagoon area. They paid $40,000.00 for the land and when they were first thinking of selling out in 1959 they were offered $100,000.00 for it.”

Hess also explained how the dairy industry was an important part of Davis County’s economy given its location between Salt Lake City and Ogden saying Paramount Dairy was “one of the largest wholesale milk producers in the country.” About 500 cows were milked at the dairy and milk was transported to Salt Lake City from Farmington on the 8:00 a.m. Bamberger Train. Modern facilities were added in 1950, but it’s possible they still utilized the old barns built for the race track in 1911.

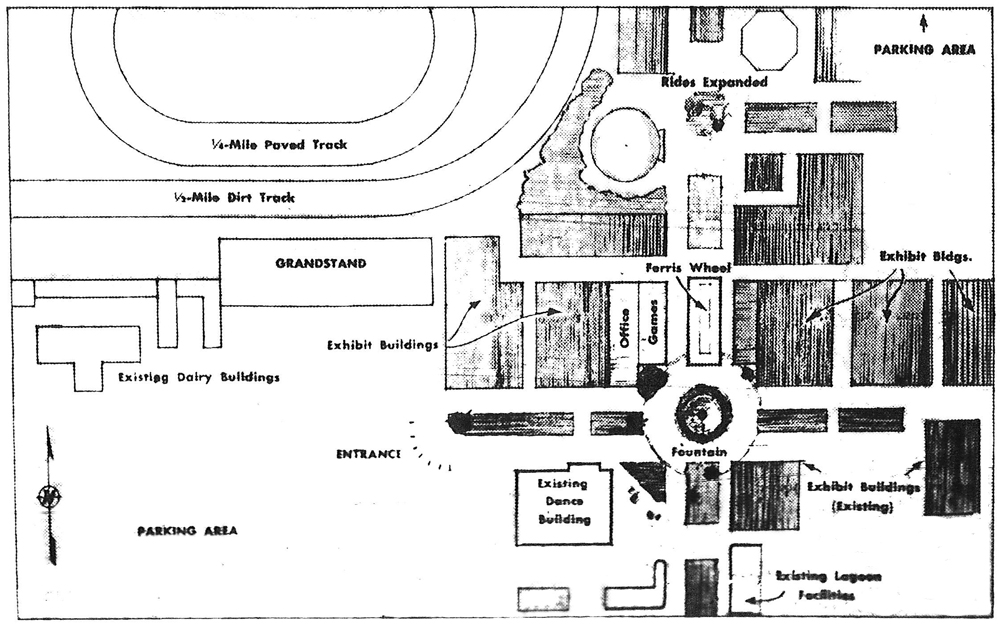

In the 1960s, racing nearly made a comeback to Lagoon in the form of stock car races. But as with horse racing, it was met with overwhelming opposition. On a fall evening of 1964, Lagoon manager Robert Freed presented to the Farmington City Council and a room full of about 250 residents the benefits of holding stock car races. He ensured that measures would be taken to minimize any negative impacts on surrounding neighborhoods and contended that the growing sport of stock car races would provide revenue for the city, add jobs and help Lagoon finance other long-range expansion efforts. The plan was to shorten the old dirt track to a half-mile, allowing the Midway to grow northward, and a paved quarter-mile track for stock cars would be added inside the dirt track with a new grandstand to serve both.

It was estimated that about a quarter of those in attendance were in favor, while many more were not. Those against it didn’t believe the noise could be properly suppressed. They pointed to examples at the Utah State Fairgrounds where nearby residents complained of the nuisance created by stock car races and depreciating land values. This was at a time when both the Utah State Fair and Davis County Fair were seriously considering relocating to Lagoon.

A week later, the Farmington City Council voted 3-2 in favor of rezoning to permit stock car racing, animal racing, rodeos and fairs at Lagoon. In response, the opposing citizens made plans to petition for a referendum. It was clear that the majority was against races in Farmington, so at the suggestion of the three council members who voted in favor of it, Lagoon withdrew their request for stock car racing. The land was still rezoned to allow other events coinciding with state and county fairs, but would not include any mechanized racing.

The first Davis County Fair was held at Lagoon in 1906 and later became an annual event starting in 1929. When the park closed in World War II the fair moved to Kaysville. As neighborhoods closed in on the Kaysville fairgrounds, the Davis County Fair began looking for a new location once again. Lagoon had grown in popularity since reopening after the war and the fair returned there in 1966. New buildings were constructed at Lagoon to accommodate the fair including a concrete grandstand, built in the same general area that the first grandstand was built in 1911. It was first known as Davis Stadium. When it wasn’t utilized for the fair, it was used for weekly rodeos, demolition derbies and even Boy Scout jamborees.

Davis County leased the land from Lagoon for the fair. When that lease was about to run out in the ’80s, Lagoon still wanted to host the fair and even talked about donating the land for that purpose. Still, it was ultimately decided that the fair would move once again.

The last county fair at Lagoon was in 1984. With the animal pens gone, Lagoon began to expand on the areas which had been set aside for the fair for the past two decades. Construction started right away on a new 40,800-square-foot maintenance building on part of the former fairgrounds.

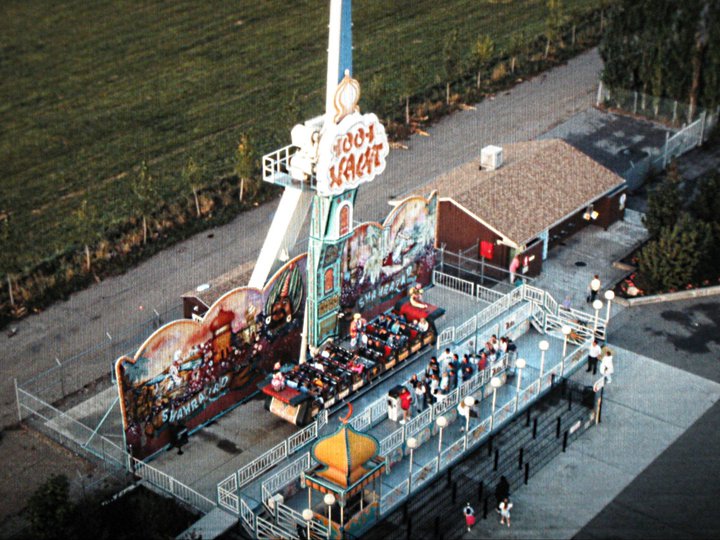

The Midway stretched further north past Boomerang, Sky Ride and Jet Star 2 in 1986. Flying Carpet and Flying Aces were installed that year inside the area that used to be the Race Track. By then the name had changed from the Davis Stadium to the Lagoon Stadium and was still used for occasional concerts and as a place to watch fireworks shows on July 4th and 24th.

In the mid-1990s, Lagoon once again sought approval for a different form of racing at the park and once again, nearby residents were concerned about the noise it would create. This time, the plans were for a controlled drag strip that allowed park guests to race each other. But it didn’t cause the kind of uproar created by horse racing in the 1910s or stock car racing in the ’60s. Lagoon already planned to make modifications to lower the noise level by having special mufflers installed on the dragsters and a 12-foot-high berm added along the north side of the drag strip. Top Eliminator Dragsters opened in 1996 along the same piece of land that was formerly the home stretch of the old Race Track.

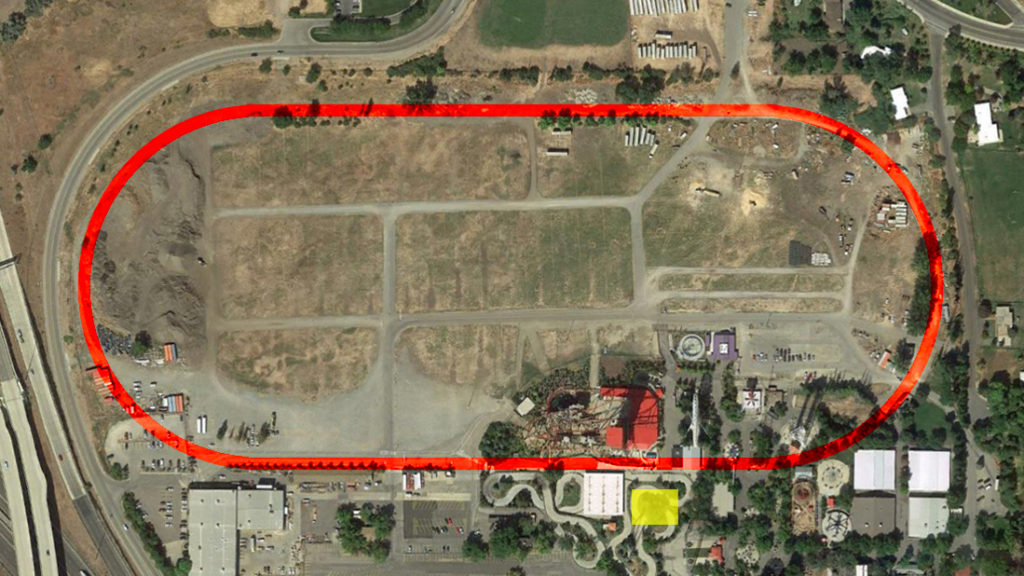

A ghost of the old track layout is still discernible in the field to the north of the park thanks to decades of use by company vehicles. Part of the short pathway that curves around the old location of Hydro-Luge also follows the track. The old white barn used by Paramount Dairy was used for storage for many years. Eventually the roof started caving in and the barn was torn down on 16 March 2015. Now only one dairy barn remains near the park’s maintenance shop.

NOTES

1. Milton’s wife, Margaret, related the following story in her historical account of Farmington:

“Milton started making the race track and found about six graves the horses would be running over. When he told Mr. Dandrun about it, he was advised to go up and tell the families they belonged to that the bodies would be moved to the cemetery and it wouldn’t cost them a penny, but the Smith family said to leave them there. Milton suggested they move the racing track farther to the east, leaving the graves unmolested and inside the track so the horses wouldn’t be running over them. This plan was followed and the graves are still there.”

The graves belonged to William O. Smith (one of the first settlers of the area) and two of his children. Even though a memorial at the Farmington City Cemetery states the bodies are still located north of Lagoon, they are supposedly no longer in the race track area. But that has yet to be confirmed either way.

2. A race between Oldfield and Beachey at the Iowa State Fair that same year can be viewed on YouTube.

MORE LAGOON HISTORY

REFERENCES

Lagoon Speed Carnival newspaper ad. Deseret News, 3 Sep 1920.

Unknown Vandals Attempt To Wreck Big Racing Cars. Deseret News, 6 Sep 1920.

Paramount Dairy Plans Two-Day Barn Party. Deseret News, 3 Sep 1950.

Blodgett, Gary. Auto Racing At Lagoon? Deseret News, 1 Oct 1964.

Blodgett, Gary. Farmington’s Council Okays Lagoon Racing. Deseret News, 8 Oct 1964.

Racing Opponents Prepare Petitions. Deseret News, 12 Oct 1964.

Blodgett, Gary. No Lagoon Racing. Deseret News, 13 Oct 1964.

Hess, Margaret Steed. My Farmington: A History Of Farmington, Utah: 1847-1976. Helen Mar Miller Camp. Farmington, Utah, 1976.

Hills, Bruce. Winter hasn’t slowed the work at Lagoon. Deseret News, 5-6 Feb 1985.

Westergren, Bruce N. Utah’s Gamble with Pari-mutuel Betting in the Early Twentieth Century. Utah Historical Quarterly 57, number 1, page 4. Winter 1989.

Leonard, Glen M. A History Of Davis County. Utah State Historical Society, Davis County Commission, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1999.

William Orville Smith. FindAGrave.com, updated 8 Jul 2010.

Mack Jay Knight obituary. Deseret News, 24 Oct 2013.

Horse Racing History. WinningPonies.com, accessed 4 Mar 2015.

© Braden Miskin

Leave a Reply