There have been numerous ideas for Lagoon attractions, many of which never made it past the concept or planning stages. This article is part of a series about some of those plans that failed to become a reality.

In 2025, Lagoon opened The District, which is the most ambitious development in Pioneer Village since the 1990s. The District consists of two brand new rides and modifications to an existing ride.

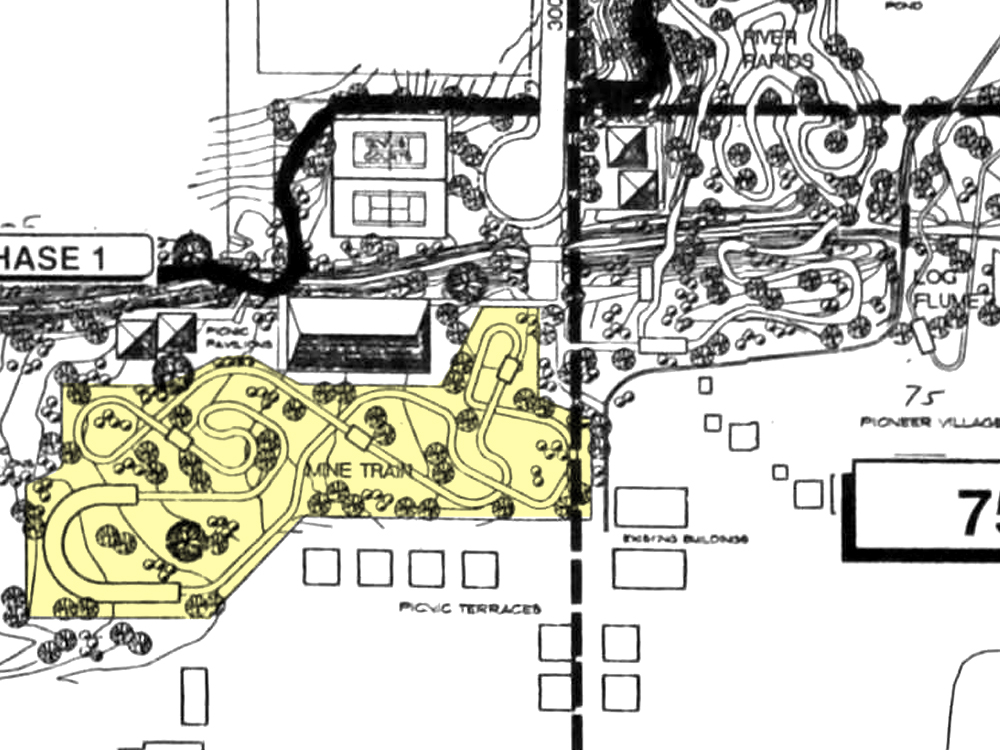

In the ’90s, Lagoon’s plans for Pioneer Village also involved two brand new rides and modifications to an existing ride. But those earlier ideas were on such a large scale, it would require an expansion of the park and partial closure of a city street.

Maybe it was because those earlier plans were so extensive that only one ride ever materialized. A river rapids ride, which was at one time referred to as Snake River Rapids, took years to build and opened as Rattlesnake Rapids in 1997.

Also being considered at the time was an extension of the Log Flume. Lagoon’s Log Flume was purchased from a short-lived park on the Oregon coast. It was one of the smallest flume rides available and was notorious for its slow-moving queue. In the days before Rattlesnake Rapids and other water rides at the park, the Log Flume was a major draw on hot days and would’ve benefited greatly from a higher ride capacity.

PROSPECTING

The other addition on the drawing boards for Pioneer Village’s expansion was a mine train coaster. The world’s first mine train coaster opened in 1966 at Six Flags Over Texas. It was designed by Arrow Development, the company that was instrumental in helping to design and build many of Disneyland’s earliest rides. It was after working on the world’s first tubular steel coaster (the Matterhorn Bobsleds) when Arrow hired their first employee to have a college degree in engineering, Ron Toomer, to design the Runaway Mine Train for Six Flags. Its popularity spawned similar roller coasters at parks everywhere over the following decades.

Lagoon’s Pioneer Village was a perfect thematic setting for this type of ride and it would’ve been the park’s first major coaster since Colossus was added in 1983. While there was never any indication of what company would design the mine train for Lagoon, it seems that Arrow could have been a contender.

In the time since Ron Toomer designed that first mine train coaster for Six Flags, he went on to work on the first steel looping coaster, the first roller coaster to reach 200 feet tall and several other industry milestones.

Meanwhile in 1977, Arrow Development (later Arrow Dynamics) had relocated from California to Clearfield, Utah – about 12 miles from Lagoon. Ron Toomer would also move to Utah in 1984. In 1986, Arrow hired a local named Dal Freeman to be their new director of engineering.

It may seem like Arrow was an obvious choice to work with Lagoon on a mine train or any other type of coaster. But the only clue that it may have ever happened is when Ron Toomer revealed his own hopes in a 1995 interview to someday see one of his coasters at Lagoon.

Toomer retired in 2000 and Arrow went bankrupt the following year. The company’s last project was built in Utah, but it wasn’t a roller coaster for Lagoon. It was the tower for the 2002 Winter Olympics cauldron. In the end, the Log Flume (engineered by Toomer) and Speedway, Sr.’s update in 1969 were Arrow’s only rides to ever operate at Lagoon.

STAKING A CLAIM

Part of the reason that Lagoon needed to expand was due to the introduction of Lagoon-A-Beach in the late ’80s. The water park was larger than the old Swimming Pool area that it replaced. A pathway between the old jail and the Gingerbread House used to connect Pioneer Village to the rest of Lagoon. That path was removed to allow for much-needed space inside Lagoon-A-Beach. This cut off the circulation of Pioneer Village’s north end, making it a kind of dead end in the park.

Back then, a low-use public road named Lagoon Lane ran along the east side of the park’s boundary north of Pioneer Village and east of the picnic terraces. Lagoon purchased property on the other side of Lagoon Lane, in hopes of expanding that direction.

In 1991, the Deseret News reported on the plans Lagoon had for the land they had purchased outside the park. Since it was separated from the rest of the park, Lagoon asked the City of Farmington to close a portion of Lagoon Lane to allow for the park’s growth. In exchange, Lagoon constructed the Lagoon Trail as a public walking, cycling and equestrian trail.

The expansion would move the park’s boundary closer to Farmington’s quiet, residential Main Street. Because of concerns for potential noise and change in atmosphere near the city’s historic center, ride structure height restrictions were discussed at length during city meetings in 1992. The restrictions that were settled upon dictated that rides could be no taller than 75 feet in the area north of 300 North, where the mine train was planned to be built. This still provided plenty of height for a decent mine train coaster. (By comparison, the wooden Roller Coaster is 62 feet tall).

The space designated for the coaster stretched all the way from the north end of Pioneer Village to the area near the historic Lake Park Terrace and the Victorian-style Opera House Square. There is unfounded speculation that there was once a vague idea to connect or create a transition between the two areas. Opera House Square opened years before Lagoon ever considered acquiring Pioneer Village and it was decorated with authentic furniture and other antiques, similar to the buildings in Pioneer Village. Interstingly enough, the Opera House was featured prominently on various Pioneer Village souvenirs in the ’70s, even though Opera House Square was about 500 feet away. The mine train coaster could’ve helped fill that gap.

WHY DIDN’T IT PAN OUT?

It seems the focus was always on the river rapids ride with the mine train left as a follow-up possibility. A news article in 1991 said the mine train coaster was only tentatively planned for “the far future”.

One thing that may have kept Lagoon from thinking more seriously about a mine train was the fact that Rattlesnake Rapids ended up costing $7 million, making it the park’s most expensive ride by far, up to that time.

Another factor may have had something to do with the race that was heating up in the amusement industry to develop more extreme thrill rides. It was the middle of what has been called the Coaster Wars, when advancing technology was allowing coasters to reach faster speeds and climb to heights of 200, 300 and 400 feet in the air.

For a smaller park, Lagoon kept up the best way it could, with towering, non-coaster thrill rides like Sky Coaster, The Rocket and Catapult, all over 200 feet tall and all added within a seven-year period. In about the same length of time, Lagoon also added more coasters in quicker succession than ever before. But Wild Mouse, The Spider and The Bat weren’t really record-breakers.

While Lagoon never had any coasters from Arrow Dynamics, they did get Arrow’s former director of engineering. Dal Freeman grew up on a farm in Salt Lake and went to school at the University of Utah. At Arrow Dynamics, he had worked on some of the record-breaking coasters that Ron Toomer was working on.

Dal joined Lagoon around 1997 and would be involved in every new ride after that, becoming integral in the creation of a string of one-of-a-kind coasters for the park. The first of these was Wicked in 2007. This launch coaster ended Colossus: The Fire Dragon’s 24-year reign as the park’s tallest and fastest roller coaster. At a cost of $10 million, it also topped Rattlesnake Rapids as the most expensive ride at Lagoon.

After the success of Wicked, each of Lagoon’s following roller coasters were increasingly unique and would involve more partnerships with local manufacturers. Bombora opened in 2011 followed in 2015 by another record-breaker, the 208-foot-tall Cannibal. Upon its completion, Dal Freeman retired.

A FLASH IN THE PAN

Three decades and several new coasters later, the idea of a mine train coaster seems to have been long forgotten. The rusty tracks and old mine carts throughout Rattlesnake Rapids seem to serve as a silent reminder of what might have been.

The park’s expansion in the ’90s did allow for circulation to return to the north end of Pioneer Village, but the one new attraction, Rattlesnake Rapids, was built on land the park already owned and had been using for the Stagecoach ride. What about the land that was actually added?

An October 1991 Deseret News article stated that if the mine train ride didn’t materialize, “Lagoon might put several children’s rides there.”

Kiddieland has struggled with space for decades, but when it expanded in the late 2000s, it was onto the former miniature golf course area. No rides have ever been installed on the land once earmarked for the mine train coaster.

Instead, the area was used for added picnic space. Six picnic terraces were built on the southern end of the area in 1993 with many more added to the north over the next few years.

Picnicking at Lagoon is a tradition that goes back to the 19th century and group events continue to be a major source of revenue for Lagoon. The added terraces are well-used and the area provides a relatively quiet retreat from the screams and roaring coasters of the Midway. And if somehow the possibility for a ride in that spot ever comes up again, it would be relatively easy to replace the terraces. So far, however, plans for a mine train coaster have never surfaced publicly again.

When Pioneer Village opened at Lagoon in 1976, it included five rides. Over the years, different rides have closed for various reasons. For a while, Rattlesnake Rapids and the Log Flume were the only two rides in Pioneer Village. The unexpected retirement of the Log Flume in 2022 created an opportunity to add something new to Pioneer Village without requiring more space. The District brings the ride count for the Village back up to four, which is more than there have been since the 1980s.

MORE LAGOON HISTORY

REFERENCES

Rosebrock, Don. Farmington to discuss Lagoon petition. Deseret News, 18 Apr 1989.

Dal Freeman. Directions, 1989, Vol. 3, No. 2.

Padilla, Steve. Roller Coaster War Flexes Technology. Los Angeles Times, 3 Apr 1990.

Rosebrock, Don. Lagoon seeks to use street in Farmington for expansion. Deseret News, 22 Jan 1991.

Arave, Lynn. Farmington approves partial road closure to let Lagoon expand. Deseret News, 25 Oct 1991.

Rosebrock, Don. Lagoon trail system clears a hurdle. Deseret News, 11 Mar 1992.

Associated Press. Utahn designs rides that terrify. Deseret News, 22 Jun 1994.

Arave, Lynn. King of the Coasters. Deseret News, 21 Jul 1995.

A Historical Overview of Arrow Development. ArrowDevelopment.blogspot.com, 23 Apr 2014.

Dal Freeman – Saved the best for last. ArrowDevelopment.blogspot.com, 16 Jul 2015.

Coaster Landmark – Runaway Mine Train. ACEonline.org, accessed 9 Apr 2025.

Roller Coaster History – Timeline. UltimateRollerCoaster.com, accessed 6 May 2025.

Leave a Reply