This is the first in a two-part series about the 1953 fire and the New Lagoon that rose from the ashes.

Lagoon, just like any business that’s been around for over 135 years, has had to adapt in the face of unexpected events. Even in its first six or seven decades, Lagoon went through many changes.

Like when the water level of the Great Salt Lake dropped just a matter of years after the Lake Park bathing resort opened on its shore in 1886. While several of the other shoreline resorts were shuttered and forgotten, Simon Bamberger moved Lake Park’s buildings next to a man-made “lagoon” and his new passenger rail line for easier access and a constant body of water for boating and swimming.

In the 1910s and ’20s, Lagoon transitioned into a full-fledged amusement park when they began adding more thrill rides, similar to other parks across the country which had previously focused on attractions like boating, dancing and picnicking.

The Great Depression in the 1930s took a toll on parks nationwide. The number of amusement parks in the United States dwindled from over 2,000 in 1910 to fewer than 500. Things slowed down a bit at Lagoon too, but it remained open each year. It wasn’t until the lack of materials and rationing of gasoline during World War II that Lagoon was forced to close in the mid-1940s.

Then in 1946, the Freed brothers and Ranch Kimball leased the park from the Bamberger family and gradually brought it back to life. New buildings and rides were added over the following years.

Things were going well by the 1953 season. That year, a new Ferris Wheel was installed on the Midway and the Penny Arcade was enlarged. New lawns and gardens were planted on the east side of the park and the Roller Coaster was coated with three and a half tons of white paint.

After Labor Day, the park closed up for the season and settled into its usual routine with rides and equipment moved into storage and everything prepped for winter. No one suspected that the park was about to go through one of the biggest turning points in its history.

About a month and a half after the park closed, on the evening of Saturday, 14 November 1953, park manager Bob Freed and his wife were in Salt Lake City at the home of Robert Cutler, Lagoon’s advertising director. Robert and his wife were newlyweds and it was their first time entertaining guests. As Cutler recalled, Bob received a phone call that evening from his father-in-law who lived in Farmington with the news – Lagoon was on fire!

The fire department and resident caretaker had already been alerted by then. Bob and his wife headed for the park right away. Cutler remembered that “Bob’s great concern was for the roller coaster and the carved merry-go-round horses.”

Bob’s brother Peter remembers having already gone to bed when he got the phone call. “Coming out to Lagoon, my heart started beating so hard I was afraid something would happen to me. I pulled over to the side of the road, took some deep breaths.” When he showed up to the park, he recalled that it was “an absolute madhouse”.

Firefighters opened hydrants to fight the blaze, but there was hardly any water pressure. If the fire had taken place during the summer, water from the million-gallon swimming pool or the man-made Lagoon Lake would’ve been useful in dousing the fire more quickly, but being mid-November, both had been drained for the off-season. Farmington Creek, just east of the park, was also considered, but it was too far away from the fire.

According to the Deseret News:

“Clifford Rampton, chief of the Bountiful Fire Department, ordered a hole knocked through a cement pipe near the lake to obtain sufficient water pressure. This action possibly saved the roller coaster.”

Efforts were also slowed at first by flashing arcs and falling power lines until electricity at the park could be turned off. Bursting oil drums caused flames to shoot higher at times. It was feared that an underground gasoline storage tank near the Dancing Pavilion might also explode, but luckily never did.

Multiple fire departments were called on to help that night. It was estimated that about 500 volunteer firefighters arrived from several different agencies – Farmington, Bountiful, Kaysville, Clearfield, Naval Supply Depot, Hill Air Force Base and Davis County. Firefighters kept working until around 4 a.m., but kept equipment on the scene all night.

At the peak of the fire, the sky above Lagoon turned a “dull red” with flames about 300 feet high that attracted spectators from as far away as Ogden and Magna. They arrived by the carload, many stopping along the new freeway and blocking traffic for about a mile in each direction. State troopers and county policeman worked for four hours to control the crowds of onlookers.

Those controlling the crowds later mused that the entire cost of damages to the park could have been covered if everyone who came to watch the fire had paid a dime each for admission.

Margaret Hess, a long-time Farmington resident and wife of Milton Hess (who helped build most of the buildings at Lagoon before the fire) shared their perspective of the event:

“In 1953 a terrible fire destroyed a lot of the things Milton had built at Lagoon. He would not even go down to see it that night. He was heartsick to know so much or so many things, that had taken years to build, had been destroyed in such a short time.”

The fire spread rapidly because of a south wind, and burned the entire west section of the park: the Fun House, the Dance Pavilion, Shooting Gallery, the Prize Center, the Cafe, and many little buildings. Also destroyed were many rides, benches, chairs, and tables, etc., that were stored on the Dance Pavilion for the winter. All the beautiful shade trees were destroyed. Some had been planted since 1896.”

The buildings along the east side of the Midway were mostly undamaged, but still affected by the heat of the flames. As it reached a building north of the Midway which housed Lagoon’s offices, crews quickly removed furniture and equipment from the building in case it also caught fire, but only one of the building’s windows shattered because of the heat. Unexplained damage was found inside afterwards, however. Things like telephones, cabinets and lighting fixtures were torn from the walls and nobody seemed to know if it was caused by firefighters or vandals, but the damage was estimated to be hundreds of dollars for the destruction in the office alone.

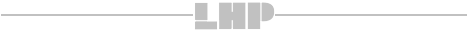

To save the antique Carousel, it’s said that Bob Freed kept a steady stream of water over the roof. Black scorch marks can still be seen on the underside of the roof to this day.

By the next morning, most of the spectators had gone, but the charred remains were still smoldering that afternoon.

“My father was a fireman at the Naval Supply Depot (Freeport) and he took me down to see it…He was not on duty that night so he wasn’t involved in fighting the fire. While he went inside to talk to the firemen he left me on a tall, white wooden fence just west of the park office. From there I could see what was left of the Fun House, I remember it well as we had just been in it a few weeks before. Everything else was just black. But beyond the black I could see the booths and rides, so I felt a little better, because all was not lost. By the time we went down most of the people had left, a few remained.”

Scott Van Fleet

A former manager once related that the cause of the fire was never truly determined, but it was speculated to have started in either the chain house of the Roller Coaster or in the backroom of The Ghost Train dark ride, which was immediately south of the coaster’s station.

The park’s losses were estimated to be at $500,000 (equivalent to over $5 million today) and was only partially covered by insurance. It was the largest fire at Lagoon and, even with occasional floods and windstorms, probably the most destructive disaster in the park’s history.

Much of the older parts of the park were gone along with some of the improvements made by the new management. Given what the work they had put into the park since re-opening it in 1946, it’s understandable why they were determined to have it rebuilt and open on time the next spring.

Continue to part two – The New Lagoon

GALLERY

The Lagoon History Project is a non-profit resource for info about Lagoon Amusement Park, unaffiliated with Lagoon Corporation. Thanks to your donations and other support, this resource is made available for free, without all the intrusive ads, pop-ups and cookies found on so many other websites today.

You can help keep it that way by donating via Venmo or PayPal…

MORE FROM LHP

SOURCES

Jones, Vard. Lagoon Will Rebuild Fire-Razed Midway. Deseret News, 16 Nov 1953.

Lagoon Office Havoc Studied. Deseret News, 16 Nov 1953.

Fire Raged as Water Supply Failed. Deseret News, 16 Nov 1953.

‘Admission’ to Lagoon Fire Could Defray Loss. Deseret News, 16 Nov 1953.

Salt Lake Funspot Hit by 500G Blaze. The Billboard, 28 Nov 1953.

Blodgett, Gary R. Lagoon Chief Cites Improvements, Predicts ‘Most Promising Season’. Deseret News, 6 Apr 1963.

Hess, Margaret Steed. My Farmington: A History Of Farmington, Utah: 1847-1976. Helen Mar Miller Camp. Farmington, Utah, 1976.

Freed Chavre, Jo Ann. The Bob Book: A Collective Memory of Robert E. Freed. Salt Lake City, Utah, 1999.

Lagoon: Rock And Rollercoasters. KUED, Jun 2016.

Great Moments. NAPHA.org, accessed 14 Nov 2021.

Email to author, 20 Oct 2005.

Emails to the author from Scott Van Fleet, Sep 2014.