This is the second in a two-part series about the 1953 fire and the “New Lagoon” that rose from the ashes.

“We could see our entire business going down the drain that morning of the fire. But actually, it created a situation that forced us to remodel not only the burned out area but the entire midway.”

“After the fire our crews went on overtime and rebuilt much of Lagoon. We opened on schedule the following May with every board in place.”

Robert E. Freed, former Lagoon manager

Lagoon re-opened for a “pre-season pre-vue” in early May 1954, a little less than six months after an expansive stretch of the park burned to the ground. In that short time, nearly all of the damaged rides and buildings had been repaired or replaced. Formal opening ceremonies were held later that month at the beginning of Memorial Day Weekend.

Dignitaries in attendance included Maurine Parker (Miss Utah), Governor J. Bracken Lee and mayors and city officials from around Davis County, Ogden and Salt Lake City. Cutting the ribbon at the new entrance was Joseph S. Clark who used to own part of the land Lagoon sits on and sold it to Simon Bamberger in the 1890s, and who was also at the first Lagoon opening. Below is a list of what changes could be found by guests returning for the 1954 season.

1954 ADDITIONS & IMPROVEMENTS

- Patio Gardens replaced the Dancing Pavilion

- Roller Coaster station rebuilt and new trains added

- Carousel sanded down and repainted

- Spook House replaced The Ghost Train

- A new Shooting Gallery replaced the old one

- Tilt-A-Whirl replaced an older model

- Roll-O-Plane replaced one that opened in 1947

- Rock-O-Plane was added

- Octopus was added

- New and enlarged Prize Center

- Maintenance shops

- New warehouse to replace older storage buildings

After a half million dollars in improvements and a temporary re-branding as New Lagoon, it was definitely a very different place compared to the previous season. But it wasn’t really the rides and attractions that were different – only the Octopus and Rock-O-Plane were completely new to the park.

What really transformed the Lagoon experience was the architecture. It was a manifestation of the Modernist movement that had been growing in Europe since World War I and picked up steam in the United States in the 1930s and ’40s.

A MODERN LAGOON

Sometimes compared to a swinging pendulum, a culture’s dominant trends in design, art and architecture have been known to go from one extreme to the other. To younger artists and architects in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s, the Victorian look began to represent the old regime that was responsible for the wars that so many countries had just suffered through, and that young soldiers fought and died in.

Modernism was a counter-movement that pared down the traditional, heavily-ornamented styles to their functional minimum, offering a fresh sense of renewal and hope for the future. As a counter-movement, the most effective Modernist environments often include, or are juxtaposed with, some element of the previous era to enhance the contrast between the two styles.

Whether intentional or not, this contrast was achieved at Lagoon with pre-existing features like the ornate, hand-carved wood horses and decorated panels of the Carousel, and the formal gardens forming the spine of the Midway which retained the classic Edwardian/Beaux Arts garden style.

Thanks to visionary management, the Lagoon of the ’50s and ’60s was tied together by a single, unifying visual statement for the first time since its early days. But that vision actually began unfolding a few years before the fire, when a group of four brothers and their friend from Salt Lake began leasing the park after World War II.

NEW LAGOON’S TRUE BEGINNINGS

Ranch Kimball was an artist who had been implementing a contemporary style in Lagoon’s advertisements and park signage since the 1930s or earlier. He then went into business with his friends, the Freed brothers, to re-open, fix up and operate Lagoon after it had been closed during the war.

Robert Freed said of the early changes, “Ranch changed the color scheme from gray and drab to solid colors of all hues. That’s about all we did the first year and then we mapped out a long-range program.”

One of the bold and exciting color treatments Ranch gave the park was for the Carousel. The color choices may have seemed haphazard and unrelated, but there was a method to the madness. Using the mindset of a child, he chose colors for the animals like a toddler choosing random crayons to color in a coloring book. For example, the lion was repainted with turquoise fur and a purple mane. The Carousel was only thirty-something years old at the time, so the idea of preserving the original colors wasn’t as important as it would be today. The choice was clearly meant to invoke a sense of whimsy and playfulness – a new take on an old idea.

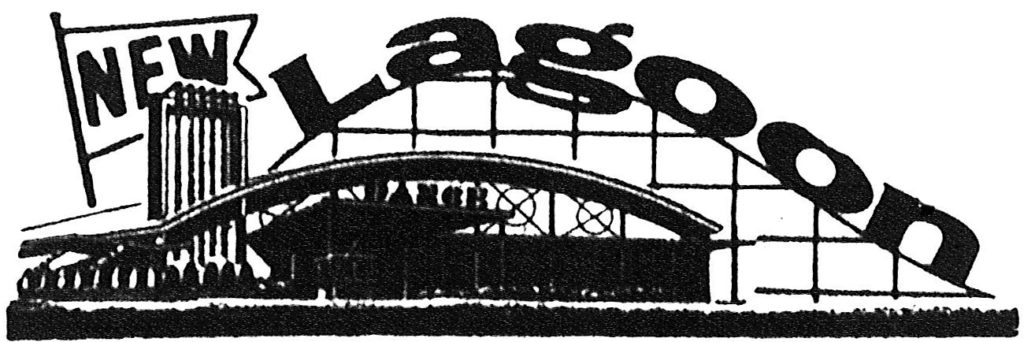

Thanks to a successful re-opening, the new management was able to revitalize existing features and add others for their second season of leasing the park – all of which shared evidence of Streamline Moderne influences. There were new buildings around the swimming pool, a new haunted dark ride and older buildings were remodeled. Sleek, futuristic rockets replaced the old-fashioned planes that swung over Lagoon Lake and a new miniature train (appropriately named the Streamliner) began the tradition of train rides around lake.

Another 1947 improvement was the auto gate (shown in the ad above). Before automobiles became the preferred conveyance to Lagoon, the Bamberger Railroad would drop guests off at the original entrance on the east side of the park. Over time, more and more vehicular parking space was added to the west side of the park near the new US Highway 91 (now Interstate 15) that rolled by on its way from California to Canada.

But even with all of the changes in 1947, there was still the west half of the Midway that didn’t quite match the bold Modern style, particularly the large Dancing Pavilion and original Fun House, which were the largest buildings at Lagoon at the time.

Whether or not there were ever plans to remodel or remove those buildings is unknown, but the fire of 1953 provided a blank slate for Modern influences when rebuilding the west half of the Midway, much like what was happening in the war-torn cities of Europe.

THE NEW MIDWAY

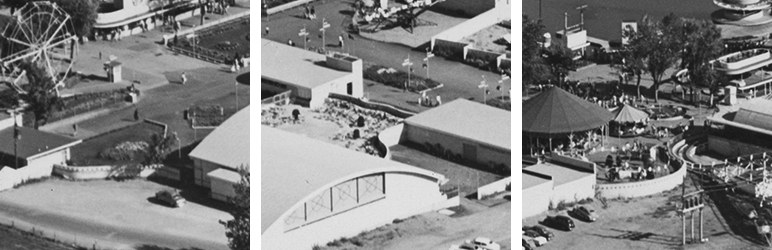

There are many signs that the overall design of 1954’s New Lagoon was considered thoroughly. The smaller buildings along the Midway shared stylistic elements with the new facades added on the east side in 1947 – rounded corners and wide, flat overhangs. The Roller Coaster station and Patio Gardens shared similar architectural features, like two bookends standing at each end of the Midway.

Both originally had open-air portions (Patio Gardens was later walled in) and exposed rib frames and trusses with a circle attached around the center of crossing members. They also both have arching, semi-cylindrical roofs, not unlike the prefabricated steel structures used in World War II because of their quick construction time and durability – features that Lagoon would’ve found beneficial as they rushed to rebuild after the fire.

Modernist architects saw buildings as a kind of machinery and designed them around their basic functions. The best instance of this approach at Lagoon was probably the new Roller Coaster station. Or at least it was the most obvious, due to its literal mechanical attributes.

The previous station hid much of the ride behind a decorative facade. The new station didn’t have walls around the loading and unloading area and the trains emerged from the front, in full view of everyone on the Midway. The new design quickly conveyed a ride, the loading and unloading and the whole process, was maximized for efficiency. Along with those simple touches, even visual cues like the smooth, rounded roofline and the flowing shapes of the canopy in front, could help “sell” a ride at a time when guests paid for each ride individually and tickets had to be budgeted wisely.

In the overall design, even spaces between the buildings were given attention. Curving concrete brick walls were added in at least three places. As shown below, these walls could be found on each side of the Patio Gardens. Another was built to follow the east curve of the Roller Coaster track then swept behind the neighboring Tilt-A-Whirl. The one on the south side the Patio Gardens (pictured in the center) later became the back wall of the Guest Services building. Lockers stand along the outside of this curved wall today.

The Patio Gardens was the replacement for the old, turn-of-the-century Dancing Pavilion that was reduced to rubble and ash in the fire. The new venue, built to the north of the Dancing Pavilion’s former location, had a ticket office out front and better acoustics inside. The stage was in the middle of the north side with a large dance floor in the middle and tables for socializing and sipping ice cold drinks. The south side of the building opened up to a large patio which served as an outdoor, starlit extension of the venue during dances and concerts. The patio was walled off on every side so that it could only be accessed through the building, but by the 1970s the outdoor space was opened up and a staircase was built up to it on the south side, which now leads up to Dracula’s Castle.

The experience of arriving at the park was also a big consideration in the new design. The 1947 auto gate was on a former east-west section of a public road called Lagoon Drive. Whether or not it escaped the fire undamaged, it was replaced in 1954 by a new auto gate to the south.

The 1954 auto gate was closer to the freeway and placed at a dramatic point so that arriving cars would be directed right at the west end of the Roller Coaster and its giant, electrically-lit sign and mountainous backdrop. The main parking lot was to the left and overflow parking was to the right, with more permanent parking being added over the years.

After leaving their cars, guests entered through the middle of the what had been the site of the old Dancing Pavilion with all-new buildings on each side. At the corner where the entryway met the Midway, there was a new L-shaped building on the north housing games and a hamburger stand. To the south was the new Octopus ride and a long building that housed the Spook House, Shooting Gallery and the Prize Center. Beyond that was a new Tilt-A-Whirl, the Roller Coaster and Rock-O-Plane. In the 1960s, a second Skee-Ball location was added on to the south end of the building and the Tilt-A-Whirl was moved elsewhere.

At first, the management considered not rebuilding the old Fun House that burned down in the fire, but quickly changed their minds. However, features and equipment that were popular in the old Fun House were hard to come by, so it didn’t open until a few years later. In 1955, the Octopus was moved over by the Carousel and construction began on the Fun House.

This brand new Fun House was finally completed in 1957. The Patio Gardens grew to be one of the premier concert venues in the area with a variety of acts that grew throughout the 1950s and ’60s. New rides were consistently introduced and the park began expanding northward in 1965.

The “New Lagoon” nickname was used for a few years and eventually dropped. Perhaps because Lagoon had firmly re-established itself and new attractions could be expected nearly every year.

Lagoon surpassed the popularity of Saltair, its chief rival for many decades. Saltair had similar beginnings to Lagoon as a 19th century lakeside resort, but had more than one major fire over the years and often suffered from fluctuating water levels before finally closing in 1958.

As for the Streamline Moderne style of New Lagoon, eventually the pendulum swung back the other way. The general feeling seems to have been that Modern buildings were becoming too common or too bland, and it’s possible more people were using the simple style as an excuse to build cheaply. It was also a time of crisis and unrest across the country and trends began feeding into more nostalgic tastes in the late ’60s and early ’70s .

Examples at Lagoon of the renewed desire to connect with the past include Opera House Square (1968) and the addition of Pioneer Village (1976). Aside from Lagoon, Trolley Square opened in Salt Lake City in the early ’70s, which was loaded with antiques and Victorian building elements salvaged from old homes and buildings in the area.

In the early ’80s, many of Lagoon’s Modernist buildings were covered up by new Victorian-style facades, a change that may have had something to do with increasing recognition of the park’s roots at a time when it was approaching its 100th anniversary.

With so many changes to the park each year, Lagoon has become a kind of visual encyclopedia of styles and trends. A lot can be learned about the history of the park and culture in general by taking a closer look.

Many of the Modern elements are still intact and could be restored fairly easily. Maybe someday there will be enough interest to bring back the style that was based on hope for a brighter future. Maybe our increasingly defeatist society could be inspired by looking back to a time when we were optimistically looking forward. One tiny hint of awareness for the Modern past of Lagoon showed up in a recent addition to the Roller Coaster. When the entrance was moved and a new locker area was added to the ride in 2018, its style mirrored the grand piano-shaped canopy of the 1954 station.

At the very least, remnants of that optimistic time period can still serve as a reminder of the fire and the defining moment it was for the Freeds and Ranch Kimball as they looked at the ashes and charred debris without letting it stop them from moving forward, giving birth to the world-renown Lagoon we know today.

Did you notice all of the annoying ads and pop-ups on this website? That’s because there aren’t any. The Lagoon History Project is a non-profit resource for info about Lagoon Amusement Park, unaffiliated with Lagoon Corporation. Thanks to your donations and other support, this resource is made available for free, without all the intrusive ads, pop-ups and cookies found on so many other websites today.

You can help keep it that way by donating via Venmo or PayPal…

GALLERY

MORE FROM LHP

SOURCES

Lagoon ad. Deseret News, 22 May 1947.

Jones, Vard. Lagoon Will Rebuild Fire-Razed Midway. Deseret News, 16 Nov 1953.

Lagoon to Open for Week-End Business May 1. Deseret News, 11 Mar 1954.

New Lagoon Has Formal Opening For 1954 Season. Deseret News, 29 May 1954.

Blodgett, Gary R. Lagoon Chief Cites Improvements, Predicts ‘Most Promising Season’. Deseret News, 6 Apr 1963.

Baird, Bonnie. Merry-Go-Round Carries A Sad Tale Of Horses. The Salt Lake Tribune, 8 Dec 1963.

Hess, Margaret Steed. My Farmington: A History Of Farmington, Utah: 1847-1976. Helen Mar Miller Camp. Farmington, Utah, 1976.

Freed Chavre, Jo Ann. The Bob Book: A Collective Memory of Robert E. Freed. Salt Lake City, Utah, 1999.

National Register of Historic Places, Lagoon Roller Coaster, Farmington, Davis County, Utah, National Register #12000885. National Park Service, 24 Oct 2012.

Hernández-Navarro, Hänsel. Art Deco + Art Moderne (Streamline Moderne): 1920 -1945. Circa, 8 Jan 2016.

Wallin, Brian. The Quonset Hut: A Rhode Island Original That Went to war – Worldwide. VarnumContinentals.org, 10 Apr 2016.

Lagoon: Rock And Rollercoasters. KUED, Jun 2016.

Rohde, Joe. Instagram post. Instagram.com, 5 Dec 2021.